Advocate Access

Get In Touch

News

Hope in Action: October 2024

Hope in Action is a series to highlight the aspects of our volunteer work. Advocacy for a child, whether in child welfare, juvenile justice, or truancy systems, covers several activities from court hearings to visits with a child to conversations with parents. Each month, we share a story of small (or big!) moments from one of our cases that exemplify what advocacy can mean to children and their families.

A SECOND CHANCE

After violating probation, 16-year-old DeAndre* was offered a second chance to successfully complete probation by the judge in juvenile justice court. To give DeAndre additional support, the judge appointed Justice-Involved Youth Advocate Graham* as his guardian ad litem.

After violating probation, 16-year-old DeAndre* was offered a second chance to successfully complete probation by the judge in juvenile justice court. To give DeAndre additional support, the judge appointed Justice-Involved Youth Advocate Graham* as his guardian ad litem.

Due to an intellectual disability, the youth struggled with self-control and executive functioning, which led to poor decision-making. He also shared with the court that he needed help controlling his anger—he sometimes acted out due to frustration.

Graham brought a TBRI® Engine Plate to his first visit with DeAndre, or Dre. Knowing Dre found it challenging to regulate his feelings, Graham used the Engine Plate to teach him how to first identify his emotions.

“The plate has been a useful tool,” Graham said. “He was immediately interested—he could easily relate to the idea of a car engine and understand the colors.”

WHAT IS AN ENGINE PLATE?

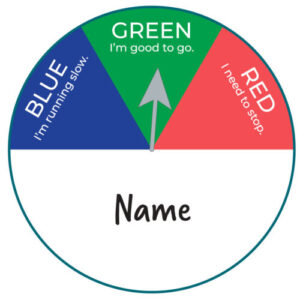

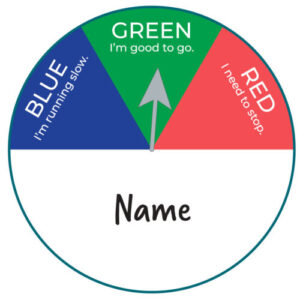

The Engine Plate is a practical tool used in Trust-Based Relational Intervention®, a trauma-informed approach to care, to help youth become more aware of their feelings so they can learn how to be in control of their bodies and behaviors. Before a child can learn to calm themselves, they must be able to identify how they feel and where they feel that emotion in their body.

The Engine Plate is a practical tool used in Trust-Based Relational Intervention®, a trauma-informed approach to care, to help youth become more aware of their feelings so they can learn how to be in control of their bodies and behaviors. Before a child can learn to calm themselves, they must be able to identify how they feel and where they feel that emotion in their body.

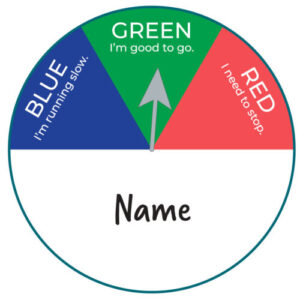

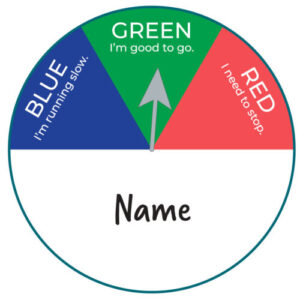

The Engine Plate uses three colors—red, green, and blue—to describe the zones people move through during the day. [See Diagram to the left.]

An “engine” on red is running too fast—it may be speeding or out of control. A person on red may have excess energy or trouble settling down. That feeling can come from anxiety, anger, distress, or overexcitement.

An engine on blue is running too slow. A person on blue may feel sad, lonely, tired, or depressed. Their body may feel heavy, slow, numb or frozen, or their mind may be distracted.

An engine on green is coasting at a good pace, like on cruise control. Someone on green feels just right and ready to learn. They are calm and prepared to handle whatever happens to them.

It’s important for youth to understand that colors are not good or bad—all people experience the three zones throughout each day. At certain times, activities require people to be in a certain zone for success. For example, before recess or a game, it helps to be on red and have high energy, and you want to be on blue before bedtime.

UNDERSTANDING EMOTIONS

After Graham explained the Engine Plate to Dre, the two worked on how to identify which color Dre was on and how those emotions felt physically as well. Graham brought the Engine Plate to every visit at the beginning of the case, using it to gauge Dre’s mood.

“It helps me know what stand of mind he’s in, and if he’s ready to talk,” Graham said. “Usually we can get to talking about the problem even if he’s not ready in the beginning, but the engine plate color helps me identify where Dre’s at with his openness at the moment.”

Before long, Dre started announcing his color as soon as Graham walked in the door, always with a grin on his face. Graham noticed that Engine Plate helped Dre understand his emotions while also giving him a small amount of control in a situation where he didn’t have a lot of say.

“Dre likes being able to say, ‘This isn’t a good time’ if he doesn’t want to discuss something,” Graham said. “It shows him that someone cares about how he feels and what he’s thinking that day. When you respect the feelings of a child, it makes them feel like their voice is heard.”

BREATHING TO REGULATE EMOTIONS

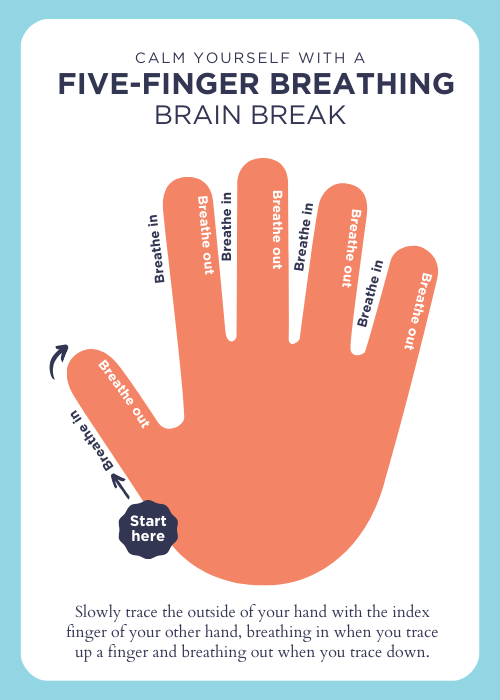

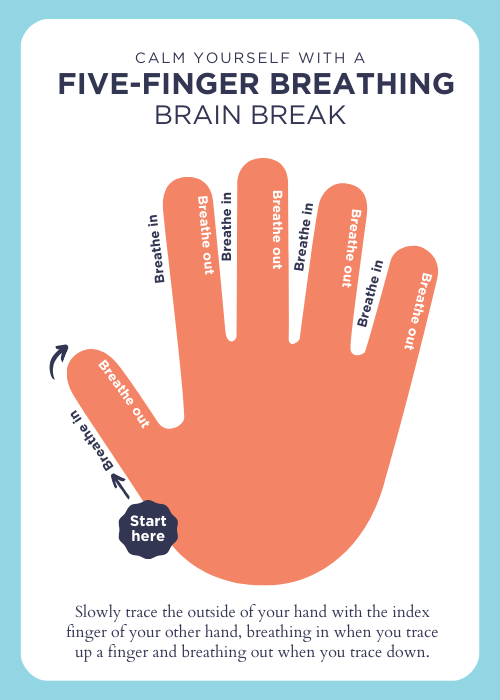

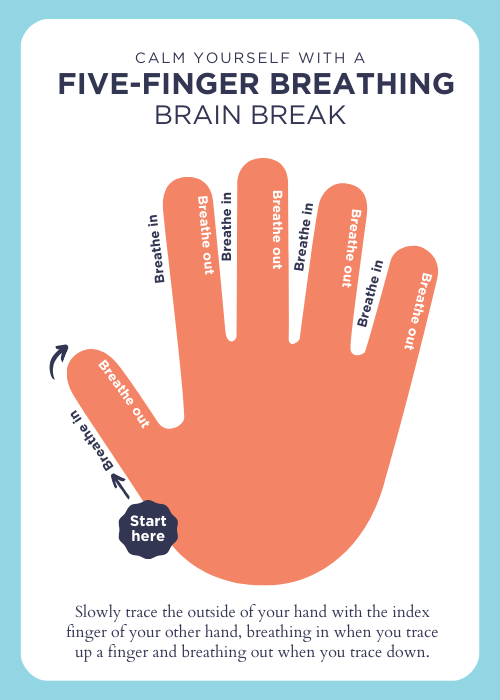

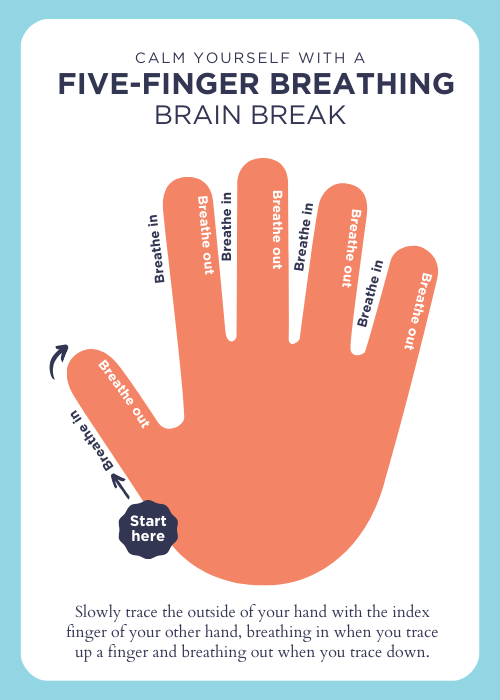

Once Dre understood how to identify how he felt, Graham introduced him to different breathing techniques to help him move colors if needed. Though he introduced him to several, including box breathing and belly breathing, Dre quickly identified “five-finger” breathing as his favorite. [See the chart to the right for instructions.]

Once Dre understood how to identify how he felt, Graham introduced him to different breathing techniques to help him move colors if needed. Though he introduced him to several, including box breathing and belly breathing, Dre quickly identified “five-finger” breathing as his favorite. [See the chart to the right for instructions.]

“We’ve talked about how the five-finger breathing engages his senses of touch, sound, and sight. It connects with his brain to help him calm down,” he said.

A SETBACK

Despite the support of his Advocate and his parents, DeAndre continued to struggle with his behavior and did not successfully complete his probation. After pleading true to multiple violations, he was ordered to the Texas Juvenile Justice Department (TJJD) for an indeterminate sentence.

Graham met with Dre after the hearing, and he was sad but in control of his emotions. He asked Graham if they could continue to meet while he was in the detention center before being transferred to TJJD. Youth stay in the county detention center for several weeks until they move to TJJD.

Though the official case would close, Child Advocates and the detention center agreed it would be in the best interest of Dre for the visits with his Advocate to continue during this waiting period, which is often stressful for youth.

Graham meets with Dre weekly during this time, continuing to listen and teach him techniques to regulate his emotions.

“I mostly help him focus on his future, reminding him that he does have a future after this,” Graham said.

TOOLS TO MOVE FORWARD

Today, Dre uses breathing to calm down when he gets upset. He will return to his room at the detention center, if he can, and focus on his breathing. Graham appreciates that he’s remembering to use breathing to regulate his body when he’s agitated—this is significant progress for a child who often reacts inappropriately when he’s angry.

The staff shared that Dre’s behavior has improved in the detention center the past few months since meeting with Graham. There are five levels of behavior—freshman, sophomore, junior, senior, honors—and Dre has moved up levels since entering detention. He still struggles with control issues and will react negatively when something happens that upsets him, but staff said he is not starting fights as often when he’s angry. He’s learning to walk away and calm himself before escalating the situation.

Moving up levels is important because the level at which a child leaves detention affects their level when they enter TJJD. This can have a long-term impact on his sentence and success at TJJD.

At a recent visit, Dre asked Graham if they could continue to have visits when he moves to TJJD, which will be in another city.

“Dre wants to continue our visits even after he leaves detention,” Graham said. “Our visits have helped him cope with all that he’s feeling as he waits to move facilities. I asked him if it was OK to share his story, and he said yes—he wants people to know having an Advocate has helped him have hope for his future, even if the ending to the case wasn’t what we wanted.”

*Names changed for privacy

object(Timber\Post)#6415 (34) { ["id"]=> int(1257) ["ID"]=> int(1257) ["object_type"]=> string(4) "post" ["wp_object":protected]=> object(WP_Post)#6333 (24) { ["ID"]=> int(1257) ["post_author"]=> string(1) "3" ["post_date"]=> string(19) "2024-10-21 16:16:39" ["post_date_gmt"]=> string(19) "2024-10-21 21:16:39" ["post_content"]=> string(8030) "Hope in Action is a series to highlight the aspects of our volunteer work. Advocacy for a child, whether in child welfare, juvenile justice, or truancy systems, covers several activities from court hearings to visits with a child to conversations with parents. Each month, we share a story of small (or big!) moments from one of our cases that exemplify what advocacy can mean to children and their families.A SECOND CHANCE

After violating probation, 16-year-old DeAndre* was offered a second chance to successfully complete probation by the judge in juvenile justice court. To give DeAndre additional support, the judge appointed Justice-Involved Youth Advocate Graham* as his guardian ad litem.

Due to an intellectual disability, the youth struggled with self-control and executive functioning, which led to poor decision-making. He also shared with the court that he needed help controlling his anger—he sometimes acted out due to frustration.

Graham brought a TBRI® Engine Plate to his first visit with DeAndre, or Dre. Knowing Dre found it challenging to regulate his feelings, Graham used the Engine Plate to teach him how to first identify his emotions.

“The plate has been a useful tool,” Graham said. “He was immediately interested—he could easily relate to the idea of a car engine and understand the colors.”

After violating probation, 16-year-old DeAndre* was offered a second chance to successfully complete probation by the judge in juvenile justice court. To give DeAndre additional support, the judge appointed Justice-Involved Youth Advocate Graham* as his guardian ad litem.

Due to an intellectual disability, the youth struggled with self-control and executive functioning, which led to poor decision-making. He also shared with the court that he needed help controlling his anger—he sometimes acted out due to frustration.

Graham brought a TBRI® Engine Plate to his first visit with DeAndre, or Dre. Knowing Dre found it challenging to regulate his feelings, Graham used the Engine Plate to teach him how to first identify his emotions.

“The plate has been a useful tool,” Graham said. “He was immediately interested—he could easily relate to the idea of a car engine and understand the colors.”

WHAT IS AN ENGINE PLATE?

The Engine Plate is a practical tool used in Trust-Based Relational Intervention®, a trauma-informed approach to care, to help youth become more aware of their feelings so they can learn how to be in control of their bodies and behaviors. Before a child can learn to calm themselves, they must be able to identify how they feel and where they feel that emotion in their body.

The Engine Plate uses three colors—red, green, and blue—to describe the zones people move through during the day. [See Diagram to the left.]

An “engine” on red is running too fast—it may be speeding or out of control. A person on red may have excess energy or trouble settling down. That feeling can come from anxiety, anger, distress, or overexcitement.

An engine on blue is running too slow. A person on blue may feel sad, lonely, tired, or depressed. Their body may feel heavy, slow, numb or frozen, or their mind may be distracted.

An engine on green is coasting at a good pace, like on cruise control. Someone on green feels just right and ready to learn. They are calm and prepared to handle whatever happens to them.

It’s important for youth to understand that colors are not good or bad—all people experience the three zones throughout each day. At certain times, activities require people to be in a certain zone for success. For example, before recess or a game, it helps to be on red and have high energy, and you want to be on blue before bedtime.

The Engine Plate is a practical tool used in Trust-Based Relational Intervention®, a trauma-informed approach to care, to help youth become more aware of their feelings so they can learn how to be in control of their bodies and behaviors. Before a child can learn to calm themselves, they must be able to identify how they feel and where they feel that emotion in their body.

The Engine Plate uses three colors—red, green, and blue—to describe the zones people move through during the day. [See Diagram to the left.]

An “engine” on red is running too fast—it may be speeding or out of control. A person on red may have excess energy or trouble settling down. That feeling can come from anxiety, anger, distress, or overexcitement.

An engine on blue is running too slow. A person on blue may feel sad, lonely, tired, or depressed. Their body may feel heavy, slow, numb or frozen, or their mind may be distracted.

An engine on green is coasting at a good pace, like on cruise control. Someone on green feels just right and ready to learn. They are calm and prepared to handle whatever happens to them.

It’s important for youth to understand that colors are not good or bad—all people experience the three zones throughout each day. At certain times, activities require people to be in a certain zone for success. For example, before recess or a game, it helps to be on red and have high energy, and you want to be on blue before bedtime.

UNDERSTANDING EMOTIONS

After Graham explained the Engine Plate to Dre, the two worked on how to identify which color Dre was on and how those emotions felt physically as well. Graham brought the Engine Plate to every visit at the beginning of the case, using it to gauge Dre’s mood. “It helps me know what stand of mind he’s in, and if he’s ready to talk,” Graham said. “Usually we can get to talking about the problem even if he’s not ready in the beginning, but the engine plate color helps me identify where Dre’s at with his openness at the moment.” Before long, Dre started announcing his color as soon as Graham walked in the door, always with a grin on his face. Graham noticed that Engine Plate helped Dre understand his emotions while also giving him a small amount of control in a situation where he didn’t have a lot of say. “Dre likes being able to say, ‘This isn’t a good time’ if he doesn’t want to discuss something,” Graham said. “It shows him that someone cares about how he feels and what he’s thinking that day. When you respect the feelings of a child, it makes them feel like their voice is heard.”BREATHING TO REGULATE EMOTIONS

Once Dre understood how to identify how he felt, Graham introduced him to different breathing techniques to help him move colors if needed. Though he introduced him to several, including box breathing and belly breathing, Dre quickly identified “five-finger” breathing as his favorite. [See the chart to the right for instructions.]

“We’ve talked about how the five-finger breathing engages his senses of touch, sound, and sight. It connects with his brain to help him calm down,” he said.

Once Dre understood how to identify how he felt, Graham introduced him to different breathing techniques to help him move colors if needed. Though he introduced him to several, including box breathing and belly breathing, Dre quickly identified “five-finger” breathing as his favorite. [See the chart to the right for instructions.]

“We’ve talked about how the five-finger breathing engages his senses of touch, sound, and sight. It connects with his brain to help him calm down,” he said.

A SETBACK

Despite the support of his Advocate and his parents, DeAndre continued to struggle with his behavior and did not successfully complete his probation. After pleading true to multiple violations, he was ordered to the Texas Juvenile Justice Department (TJJD) for an indeterminate sentence. Graham met with Dre after the hearing, and he was sad but in control of his emotions. He asked Graham if they could continue to meet while he was in the detention center before being transferred to TJJD. Youth stay in the county detention center for several weeks until they move to TJJD. Though the official case would close, Child Advocates and the detention center agreed it would be in the best interest of Dre for the visits with his Advocate to continue during this waiting period, which is often stressful for youth. Graham meets with Dre weekly during this time, continuing to listen and teach him techniques to regulate his emotions. “I mostly help him focus on his future, reminding him that he does have a future after this,” Graham said.TOOLS TO MOVE FORWARD

Today, Dre uses breathing to calm down when he gets upset. He will return to his room at the detention center, if he can, and focus on his breathing. Graham appreciates that he’s remembering to use breathing to regulate his body when he’s agitated—this is significant progress for a child who often reacts inappropriately when he’s angry. The staff shared that Dre’s behavior has improved in the detention center the past few months since meeting with Graham. There are five levels of behavior—freshman, sophomore, junior, senior, honors—and Dre has moved up levels since entering detention. He still struggles with control issues and will react negatively when something happens that upsets him, but staff said he is not starting fights as often when he’s angry. He’s learning to walk away and calm himself before escalating the situation. Moving up levels is important because the level at which a child leaves detention affects their level when they enter TJJD. This can have a long-term impact on his sentence and success at TJJD. At a recent visit, Dre asked Graham if they could continue to have visits when he moves to TJJD, which will be in another city. “Dre wants to continue our visits even after he leaves detention,” Graham said. “Our visits have helped him cope with all that he’s feeling as he waits to move facilities. I asked him if it was OK to share his story, and he said yes—he wants people to know having an Advocate has helped him have hope for his future, even if the ending to the case wasn’t what we wanted.” *Names changed for privacy" ["post_title"]=> string(28) "Hope in Action: October 2024" ["post_excerpt"]=> string(0) "" ["post_status"]=> string(7) "publish" ["comment_status"]=> string(4) "open" ["ping_status"]=> string(4) "open" ["post_password"]=> string(0) "" ["post_name"]=> string(27) "hope-in-action-october-2024" ["to_ping"]=> string(0) "" ["pinged"]=> string(0) "" ["post_modified"]=> string(19) "2024-11-20 16:27:28" ["post_modified_gmt"]=> string(19) "2024-11-20 21:27:28" ["post_content_filtered"]=> string(0) "" ["post_parent"]=> int(0) ["guid"]=> string(30) "https://endor.cplx.com/?p=1257" ["menu_order"]=> int(0) ["post_type"]=> string(4) "post" ["post_mime_type"]=> string(0) "" ["comment_count"]=> string(1) "0" ["filter"]=> string(3) "raw" } ["___content":protected]=> string(8779) "Hope in Action is a series to highlight the aspects of our volunteer work. Advocacy for a child, whether in child welfare, juvenile justice, or truancy systems, covers several activities from court hearings to visits with a child to conversations with parents. Each month, we share a story of small (or big!) moments from one of our cases that exemplify what advocacy can mean to children and their families.

A SECOND CHANCE

After violating probation, 16-year-old DeAndre* was offered a second chance to successfully complete probation by the judge in juvenile justice court. To give DeAndre additional support, the judge appointed Justice-Involved Youth Advocate Graham* as his guardian ad litem.

After violating probation, 16-year-old DeAndre* was offered a second chance to successfully complete probation by the judge in juvenile justice court. To give DeAndre additional support, the judge appointed Justice-Involved Youth Advocate Graham* as his guardian ad litem.

Due to an intellectual disability, the youth struggled with self-control and executive functioning, which led to poor decision-making. He also shared with the court that he needed help controlling his anger—he sometimes acted out due to frustration.

Graham brought a TBRI® Engine Plate to his first visit with DeAndre, or Dre. Knowing Dre found it challenging to regulate his feelings, Graham used the Engine Plate to teach him how to first identify his emotions.

“The plate has been a useful tool,” Graham said. “He was immediately interested—he could easily relate to the idea of a car engine and understand the colors.”

WHAT IS AN ENGINE PLATE?

The Engine Plate is a practical tool used in Trust-Based Relational Intervention®, a trauma-informed approach to care, to help youth become more aware of their feelings so they can learn how to be in control of their bodies and behaviors. Before a child can learn to calm themselves, they must be able to identify how they feel and where they feel that emotion in their body.

The Engine Plate is a practical tool used in Trust-Based Relational Intervention®, a trauma-informed approach to care, to help youth become more aware of their feelings so they can learn how to be in control of their bodies and behaviors. Before a child can learn to calm themselves, they must be able to identify how they feel and where they feel that emotion in their body.

The Engine Plate uses three colors—red, green, and blue—to describe the zones people move through during the day. [See Diagram to the left.]

An “engine” on red is running too fast—it may be speeding or out of control. A person on red may have excess energy or trouble settling down. That feeling can come from anxiety, anger, distress, or overexcitement.

An engine on blue is running too slow. A person on blue may feel sad, lonely, tired, or depressed. Their body may feel heavy, slow, numb or frozen, or their mind may be distracted.

An engine on green is coasting at a good pace, like on cruise control. Someone on green feels just right and ready to learn. They are calm and prepared to handle whatever happens to them.

It’s important for youth to understand that colors are not good or bad—all people experience the three zones throughout each day. At certain times, activities require people to be in a certain zone for success. For example, before recess or a game, it helps to be on red and have high energy, and you want to be on blue before bedtime.

UNDERSTANDING EMOTIONS

After Graham explained the Engine Plate to Dre, the two worked on how to identify which color Dre was on and how those emotions felt physically as well. Graham brought the Engine Plate to every visit at the beginning of the case, using it to gauge Dre’s mood.

“It helps me know what stand of mind he’s in, and if he’s ready to talk,” Graham said. “Usually we can get to talking about the problem even if he’s not ready in the beginning, but the engine plate color helps me identify where Dre’s at with his openness at the moment.”

Before long, Dre started announcing his color as soon as Graham walked in the door, always with a grin on his face. Graham noticed that Engine Plate helped Dre understand his emotions while also giving him a small amount of control in a situation where he didn’t have a lot of say.

“Dre likes being able to say, ‘This isn’t a good time’ if he doesn’t want to discuss something,” Graham said. “It shows him that someone cares about how he feels and what he’s thinking that day. When you respect the feelings of a child, it makes them feel like their voice is heard.”

BREATHING TO REGULATE EMOTIONS

Once Dre understood how to identify how he felt, Graham introduced him to different breathing techniques to help him move colors if needed. Though he introduced him to several, including box breathing and belly breathing, Dre quickly identified “five-finger” breathing as his favorite. [See the chart to the right for instructions.]

Once Dre understood how to identify how he felt, Graham introduced him to different breathing techniques to help him move colors if needed. Though he introduced him to several, including box breathing and belly breathing, Dre quickly identified “five-finger” breathing as his favorite. [See the chart to the right for instructions.]

“We’ve talked about how the five-finger breathing engages his senses of touch, sound, and sight. It connects with his brain to help him calm down,” he said.

A SETBACK

Despite the support of his Advocate and his parents, DeAndre continued to struggle with his behavior and did not successfully complete his probation. After pleading true to multiple violations, he was ordered to the Texas Juvenile Justice Department (TJJD) for an indeterminate sentence.

Graham met with Dre after the hearing, and he was sad but in control of his emotions. He asked Graham if they could continue to meet while he was in the detention center before being transferred to TJJD. Youth stay in the county detention center for several weeks until they move to TJJD.

Though the official case would close, Child Advocates and the detention center agreed it would be in the best interest of Dre for the visits with his Advocate to continue during this waiting period, which is often stressful for youth.

Graham meets with Dre weekly during this time, continuing to listen and teach him techniques to regulate his emotions.

“I mostly help him focus on his future, reminding him that he does have a future after this,” Graham said.

TOOLS TO MOVE FORWARD

Today, Dre uses breathing to calm down when he gets upset. He will return to his room at the detention center, if he can, and focus on his breathing. Graham appreciates that he’s remembering to use breathing to regulate his body when he’s agitated—this is significant progress for a child who often reacts inappropriately when he’s angry.

The staff shared that Dre’s behavior has improved in the detention center the past few months since meeting with Graham. There are five levels of behavior—freshman, sophomore, junior, senior, honors—and Dre has moved up levels since entering detention. He still struggles with control issues and will react negatively when something happens that upsets him, but staff said he is not starting fights as often when he’s angry. He’s learning to walk away and calm himself before escalating the situation.

Moving up levels is important because the level at which a child leaves detention affects their level when they enter TJJD. This can have a long-term impact on his sentence and success at TJJD.

At a recent visit, Dre asked Graham if they could continue to have visits when he moves to TJJD, which will be in another city.

“Dre wants to continue our visits even after he leaves detention,” Graham said. “Our visits have helped him cope with all that he’s feeling as he waits to move facilities. I asked him if it was OK to share his story, and he said yes—he wants people to know having an Advocate has helped him have hope for his future, even if the ending to the case wasn’t what we wanted.”

*Names changed for privacy

" ["_permalink":protected]=> NULL ["_next":protected]=> array(0) { } ["_prev":protected]=> array(0) { } ["_css_class":protected]=> NULL ["post_author"]=> string(1) "3" ["post_content"]=> string(8030) "Hope in Action is a series to highlight the aspects of our volunteer work. Advocacy for a child, whether in child welfare, juvenile justice, or truancy systems, covers several activities from court hearings to visits with a child to conversations with parents. Each month, we share a story of small (or big!) moments from one of our cases that exemplify what advocacy can mean to children and their families.A SECOND CHANCE

After violating probation, 16-year-old DeAndre* was offered a second chance to successfully complete probation by the judge in juvenile justice court. To give DeAndre additional support, the judge appointed Justice-Involved Youth Advocate Graham* as his guardian ad litem.

Due to an intellectual disability, the youth struggled with self-control and executive functioning, which led to poor decision-making. He also shared with the court that he needed help controlling his anger—he sometimes acted out due to frustration.

Graham brought a TBRI® Engine Plate to his first visit with DeAndre, or Dre. Knowing Dre found it challenging to regulate his feelings, Graham used the Engine Plate to teach him how to first identify his emotions.

“The plate has been a useful tool,” Graham said. “He was immediately interested—he could easily relate to the idea of a car engine and understand the colors.”

After violating probation, 16-year-old DeAndre* was offered a second chance to successfully complete probation by the judge in juvenile justice court. To give DeAndre additional support, the judge appointed Justice-Involved Youth Advocate Graham* as his guardian ad litem.

Due to an intellectual disability, the youth struggled with self-control and executive functioning, which led to poor decision-making. He also shared with the court that he needed help controlling his anger—he sometimes acted out due to frustration.

Graham brought a TBRI® Engine Plate to his first visit with DeAndre, or Dre. Knowing Dre found it challenging to regulate his feelings, Graham used the Engine Plate to teach him how to first identify his emotions.

“The plate has been a useful tool,” Graham said. “He was immediately interested—he could easily relate to the idea of a car engine and understand the colors.”

WHAT IS AN ENGINE PLATE?

The Engine Plate is a practical tool used in Trust-Based Relational Intervention®, a trauma-informed approach to care, to help youth become more aware of their feelings so they can learn how to be in control of their bodies and behaviors. Before a child can learn to calm themselves, they must be able to identify how they feel and where they feel that emotion in their body.

The Engine Plate uses three colors—red, green, and blue—to describe the zones people move through during the day. [See Diagram to the left.]

An “engine” on red is running too fast—it may be speeding or out of control. A person on red may have excess energy or trouble settling down. That feeling can come from anxiety, anger, distress, or overexcitement.

An engine on blue is running too slow. A person on blue may feel sad, lonely, tired, or depressed. Their body may feel heavy, slow, numb or frozen, or their mind may be distracted.

An engine on green is coasting at a good pace, like on cruise control. Someone on green feels just right and ready to learn. They are calm and prepared to handle whatever happens to them.

It’s important for youth to understand that colors are not good or bad—all people experience the three zones throughout each day. At certain times, activities require people to be in a certain zone for success. For example, before recess or a game, it helps to be on red and have high energy, and you want to be on blue before bedtime.

The Engine Plate is a practical tool used in Trust-Based Relational Intervention®, a trauma-informed approach to care, to help youth become more aware of their feelings so they can learn how to be in control of their bodies and behaviors. Before a child can learn to calm themselves, they must be able to identify how they feel and where they feel that emotion in their body.

The Engine Plate uses three colors—red, green, and blue—to describe the zones people move through during the day. [See Diagram to the left.]

An “engine” on red is running too fast—it may be speeding or out of control. A person on red may have excess energy or trouble settling down. That feeling can come from anxiety, anger, distress, or overexcitement.

An engine on blue is running too slow. A person on blue may feel sad, lonely, tired, or depressed. Their body may feel heavy, slow, numb or frozen, or their mind may be distracted.

An engine on green is coasting at a good pace, like on cruise control. Someone on green feels just right and ready to learn. They are calm and prepared to handle whatever happens to them.

It’s important for youth to understand that colors are not good or bad—all people experience the three zones throughout each day. At certain times, activities require people to be in a certain zone for success. For example, before recess or a game, it helps to be on red and have high energy, and you want to be on blue before bedtime.

UNDERSTANDING EMOTIONS

After Graham explained the Engine Plate to Dre, the two worked on how to identify which color Dre was on and how those emotions felt physically as well. Graham brought the Engine Plate to every visit at the beginning of the case, using it to gauge Dre’s mood. “It helps me know what stand of mind he’s in, and if he’s ready to talk,” Graham said. “Usually we can get to talking about the problem even if he’s not ready in the beginning, but the engine plate color helps me identify where Dre’s at with his openness at the moment.” Before long, Dre started announcing his color as soon as Graham walked in the door, always with a grin on his face. Graham noticed that Engine Plate helped Dre understand his emotions while also giving him a small amount of control in a situation where he didn’t have a lot of say. “Dre likes being able to say, ‘This isn’t a good time’ if he doesn’t want to discuss something,” Graham said. “It shows him that someone cares about how he feels and what he’s thinking that day. When you respect the feelings of a child, it makes them feel like their voice is heard.”BREATHING TO REGULATE EMOTIONS

Once Dre understood how to identify how he felt, Graham introduced him to different breathing techniques to help him move colors if needed. Though he introduced him to several, including box breathing and belly breathing, Dre quickly identified “five-finger” breathing as his favorite. [See the chart to the right for instructions.]

“We’ve talked about how the five-finger breathing engages his senses of touch, sound, and sight. It connects with his brain to help him calm down,” he said.

Once Dre understood how to identify how he felt, Graham introduced him to different breathing techniques to help him move colors if needed. Though he introduced him to several, including box breathing and belly breathing, Dre quickly identified “five-finger” breathing as his favorite. [See the chart to the right for instructions.]

“We’ve talked about how the five-finger breathing engages his senses of touch, sound, and sight. It connects with his brain to help him calm down,” he said.